|

|

The Rhythms of Salience:

A Conversation Map

|

Abstract |

Visualizing online conversation archives can reveal useful social patterns. This paper discusses design principles for social

visualizations and describes one such design in depth. |

|

| ------------- | |

Why visualize conversations? |

In the face to face world, the information we gather in a

conversation comes from the postures, glances, expressions, entrances and exits

of the participants, as well as the words they exchange. In the online world

of text-based interaction, these sensory cues to the social dynamics are

missing. The dynamics are there, but they are hard to perceive. |

|

|

Visualizing a conversation makes it possible to see these

dynamics. While the archives of written conversations cannot provide such cues

as the fleeting expressions on a listener's face, they do contain a rich,

though different, collection of contextual data. They contain cues about the

conversation structure, the relationship among the participants and their roles

in the discussion. These cues are hidden in vast files of text; by visualizing

these archives, we can make them visible.

|

|

|

A conversation archives can be the foundation for an online

community or a record of one's personal history. Having a way to easily make

sense of this material can make it far more useful: it can become a tool for

newcomers to comprehend the social environment, or for long-term participants

to grasp the nuances of the evolving relationships. |

|

|

There are many ways to visualize any dataset: the design of

a visualization depends upon the questions one seeks to answer with it. A defense

analyst may seek proscribed words or participants (Thomas and Cook 2006), while a discourse analyst may want to highlight disparities in usage (Sack 2005)[1].

In this case, the goal was to create a social visualization

-- a depiction of social data for social use (Donath, Karahalios, and Viégas 1999; Donath 2002).

Thus, we would like to know such things as: who participated? Who

was active, influential, or helpful? What was talked about, and by whom? Was it a lively or desultory discussion? |

|

|

Reading the full archive, and paying careful attention to

the names associated with each entry, might allow one to answer these

questions, but only with considerable effort and a high temporal cost. The

visualization described in this paper, The Rhythm of Salience, was

designed to create a quickly legible depiction of the conversation. The goal was

to make a single image that would summarize the key social and semantic

information in the archive, a map of the conversation. |

|

| ------------- | |

|

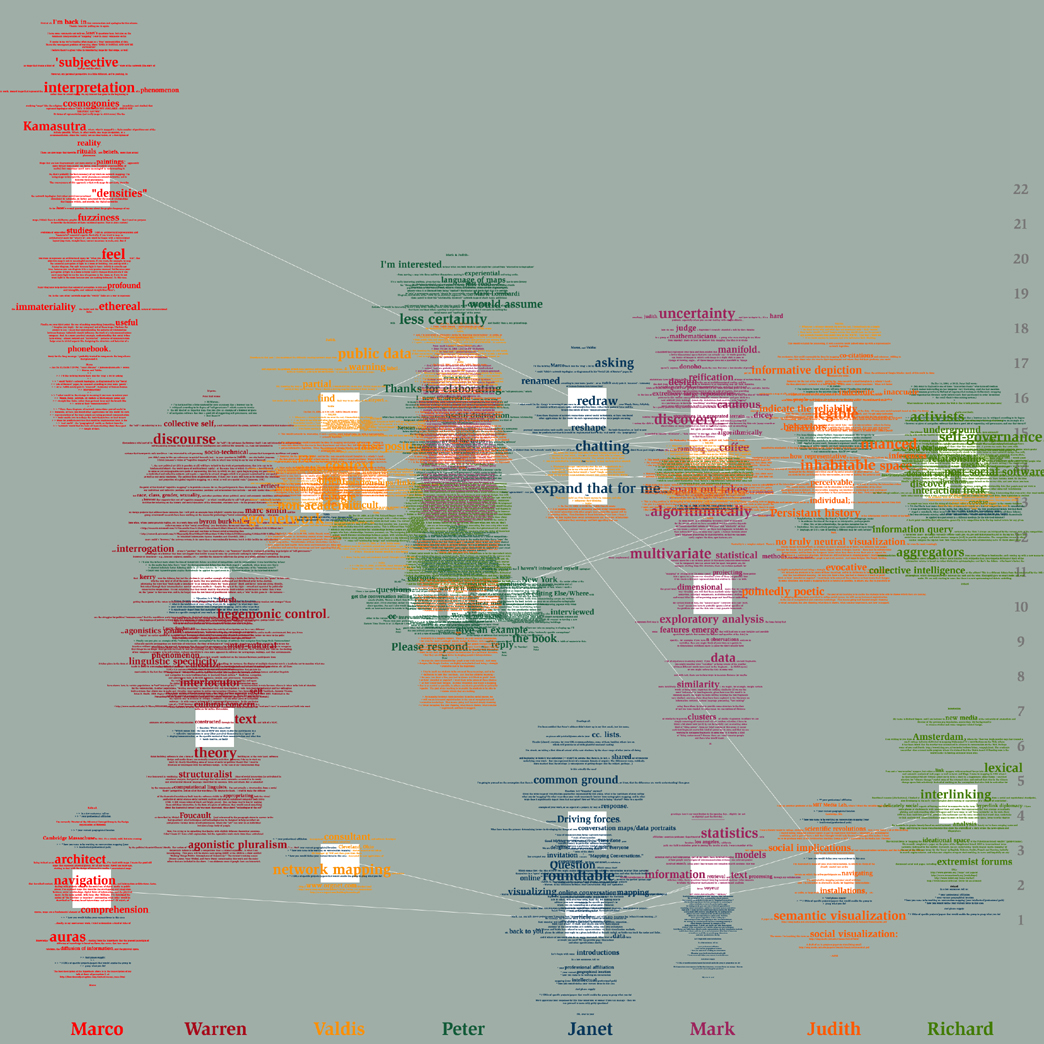

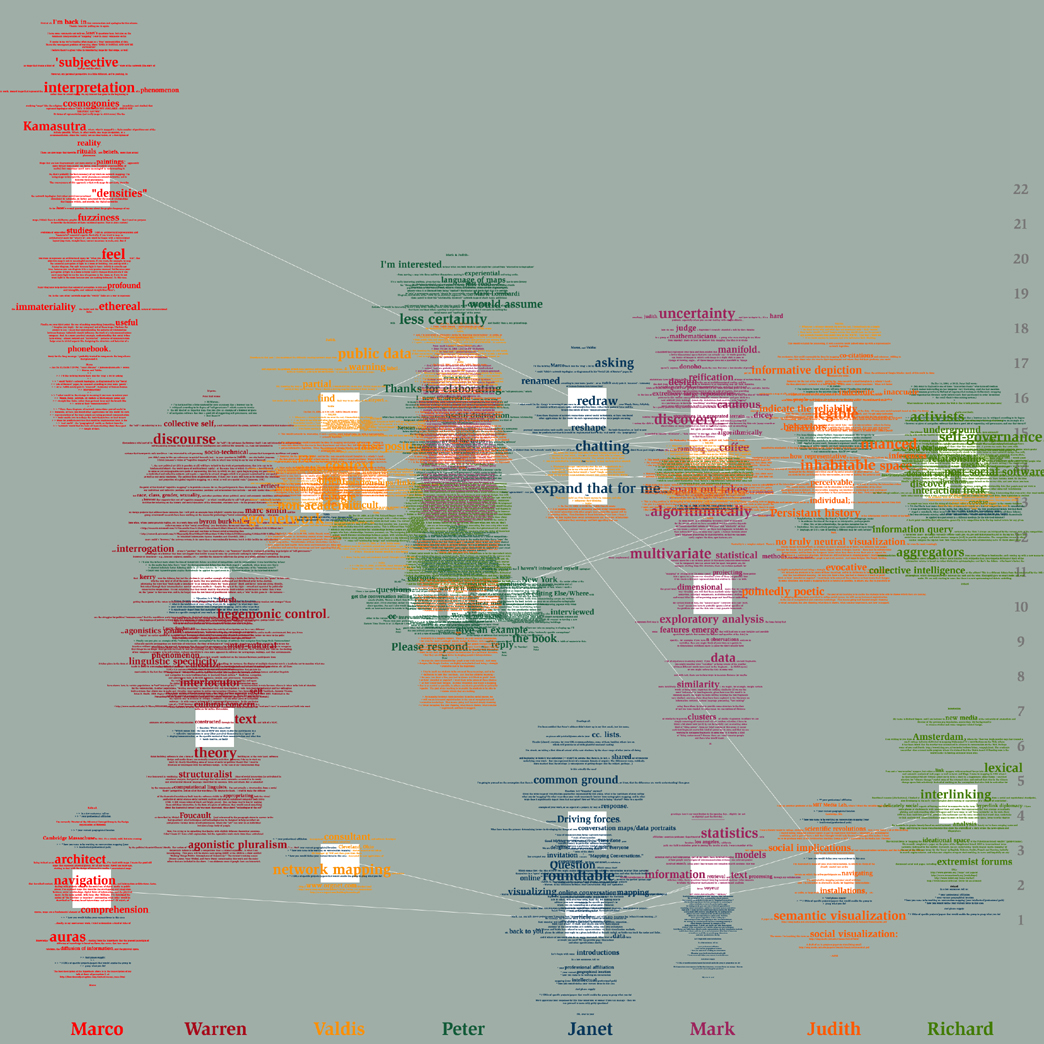

Figure 1.

The Rhythm of Salience

| |

Design Description |

The Rhythm of Salience was commissioned by Janet Abrams and Peter Hall, as part of their

book project Else/where Mapping (Abrams and Hall 2006). They invited six

researchers to participate in online conversations with them on the topic of

networks and mapping and then to visualize the resulting archive. The email

conversation took place among the eight participants over a period of 22 days,

during which a total of 30 messages were exchanged. The Rhythm of Salience

is my depiction of this discussion. | |

| ----- | |

Process and design |

This visualization was created by hand,

using Photoshop to arrange the archived text. The intent was to design a

visualization that could potentially be generated automatically, but that was

not constrained by current computational capabilities; i.e., there are clear

rules that govern the display design, though some of these rules involve

computationally complex analysis. |

|

| Several fundamental ideas guided this

design. 1) Time and temporal rhythms are important (Venolia and Neustaedter 2003), for they

provide a sense of the vitality of the conversation and the urgency with which

different messages were received. 2) It is very useful to see who are the

participants and their patterns of interaction(Donath, Karahalios, and Viégas 1999), for

this is the basic social structure of the interaction. 3) The actual text

should be incorporated into the visualization (Viégas, Golder, and Donath 2006). This

both reveals useful patterns, such as terseness or verbosity, and allows the

viewer to perceive as a unified whole the structure and content of the

conversation. | |

| The Rhythm of Salience shows this conversation as a single image, a grid where the x-axis

has a column for each participant and the y-axis represents time, with the

first day at the bottom. Each message is marked by a white square, located in

the column of the author and at the time of its posting. Thin white lines run

from message square to message square showing reply structure. | |

| The full body text of each message is

displayed, centered on the square that marks its place. Each participant's

words and name are rendered in an individual color. Quotations within a

message are shown in the color of the original author. Most of the text is

rendered in a small font, but certain phrases are featured in larger letters. These are phrases that helped portray the individual participants; phrases both

typical of and unique to that person. | |

| This design makes is possible to quickly

see the social patterns in the conversation, including the scale and temporal

rhythm of the conversation, who are the most active participants, who is

engaged with the others vs. expounding independently, who writes long missives

vs. short notes. Reading the large highlighted words provides a gist of the

conversation and a sense of the individuals' roles and direction. Although all

the text is present on this image, one would not want to try to read the

conversation in this format, for overlapping lines obscure the words. It is a

depiction for seeing overall patterns, for getting the gist of the

conversation, a sense of the participants. | |

| In the particular conversation depicted for

this commission, one can see, for example, that the conversation occurred

mainly in two bursts, the first in response to Janet's initial posting, and the

second, more than a week later, initiated by four short messages

from Peter.

This second part of the discussion was livelier, with more cross exchange and

inter-quoting among the participants. We can see that this exchange was

facilitated by Peter, whose multicolored postings are dappled with snippets

from others. And we see that Marco was a relatively isolated participant,

writing only two messages, with minimal quoting (and unquoted by others,

probably because of their late arrival to the discussion). | |

| From the featured words we get a sense of

the participants as individuals. Peter and Janet, the hosts of the discussion,

used phrases such as expand that for me, “common ground”, “please respond”,

and “thanks for elaborating”, while the other six writers used phrases that

showed their particular approaches to conversation mapping: “Multivariate”,

“exploratory analysis”, “information retrieval” and “uncertainty” come from the

words of Mark, a statistician, while “hegemonic control”, “agonistic

pluralism”, “linguistic specificity” and “interlocutor”, are from Warren, a

media theorist and linguist. | |

| ----- | |

Future work: Automation |

Many features in The Rhythm of Salience could be easily

automated, including generating the basic grid, placing the white squares, drawing

the reply lines and overlaying the text. |

|

| The most challenging feature to implement would be the phrase

highlighting. The basic approach is to find phrases that occur with unusually

frequency in a given text as compared with the expectation set by frequency in

some larger base text. The base text can be the English language as a whole,

or a more restricted set. This approach is used in Themail to visualize

relationships within a user's personal archive of email (Viégas, Golder, and Donath 2006); it is the basis for Amazon.com's “Statistically Improbably Phrases” feature, which compares the phrases in one book with those found in all of that site's searchable books. | |

| In doing the highlighting by hand, I was able to bring in much more semantic

and contextual knowledge than these algorithms possess. Along with using

unusualness as a metric for weighting, I also looked for a body of topically

coherent words. For instance, "data" is not such are rare phrase, but in the

context of Mark's other phrases, e.g. "multivariate","clusters", "features

emerge", it gained salience as part of a cluster of mathematical, statistical

and analytically oriented phrases. More challenging would be to automate the

highlighting of phrases such as “please respond”, and “I'm interested” -- words

that together illustrated Peter's role as conversation facilitator, but which

are not particularly unusual phrases in the context of ordinary usage. | |

| Automating the phrase highlighting that was done by hand is a

linguistic analysis challenge, difficult but not impossible. Although not

directly a problem in the field of visualization, it highlights this field's

need for high-quality data and interpretation. A visualization that highlight

the salient phrases in a text is useless if those phrases cannot be found. | |

| Adding interactivity to the visualization would make it possible

to differentiate among a larger number of participants and to make the full

text easily readable. Our ability to differentiate among non-continguous

colors is quite limited in the best of circumstances and in this application

the available color palette is further reduced because the chosen colors must

both render readable text and give equal weight to each participant. With an

interactive interface, one could choose a participant to highlight and then see

all instances where they are quoted by others. It would also be possible to

pick individual messages and display them in an easily readable format. | |

| ------------- | |

Summary | There are an immense

number of archived conversations. Congressional debates are in this form, as are private personal and corporate

email lists. There are big public discussions on topics from celebrity

sightings to nuclear disarmament. The utility of the archives depends upon the

tools we have for viewing them. The Rhythm of Salience shows one way of

depicting such conversations — a visualization that lets the viewer see in a

single image a complex yet legible set of temporal, personal and semantic

patterns that together create a portrait of the conversation. | |

| ------------- | |

Refererences | Abrams, Janet and Peter Hall, eds. 2006. Else/where Mapping. Mineapolis, MN:

University of Minnesota Design Institute. | |

| Donath, J.,

K. Karahalios, and F. Viégas. 1999. Visualizing conversations. Journal of

Computer Mediated Communication 4, no. 4. | |

| Donath,

Judith. 2002. A Semantic Approach to Visualizing Online Conversations. Communications

of the ACM 45, no. 4: 45-49. | |

| Sack, Warren.

2005. Discourse Architecture and Very Large-Scale Conversations. In Digital

Formations, ed. Robert Latham and Saskia Sassen. Princeton, NJ: Princeton

University Press/Social Science Research Council. | |

| Thomas, J.J.

and K.A Cook. 2006. A visual analytics agenda. Computer Graphics and

Applications, IEEE 26, no. 1: 10-13. | |

| Venolia, G.

and C. Neustaedter. 2003. Understanding sequence and reply relationships

within email conversations: A mixed-model visualization. MSR-TR-2002-102. | |

| Viégas,

Fernanda B., Scott Golder, and Judith Donath Year. Visualizing email content:

portraying relationships from conversational histories. In SIGCHI

conference on Human Factors in computing systems, Montreal, Canada, ACM

Press. | |